Notes on Motivational Interviewing

Having here praised William R. Miller, whose book, co-authored with Theresa Moyers, was unexpectedly helpful, I realized I could now go back and read Miller's famous work on motivational interviewing. As so often seems to happen with me (a phenomenon first noted by Nina Coltart), current clinical work brings certain books back to mind and unconsciously nudges them up the priority list, on which reside, at any given moment, at least a dozen other works in various stages of being read, marked, and inwardly digested. So I found my copy of Motivational Interviewing and cracked it open again.

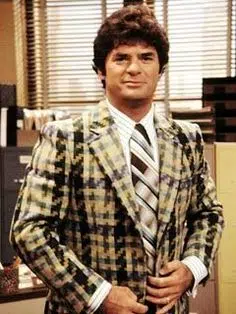

Psychoanalytic snob that I have so often been, when I first heard that phrase years ago my eyes instinctively rolled so far back into my head they were able to watch old episodes of WKRP in Cincinnati. Herb Tarlek instantly came to mind--he who was always arrayed in a hideous jacket and had the oily demeanour of the salesman that he was. That is what I thought of "motivational interviewing": some smarmy technique devised by the more revolting apologists for "dollarland," Freud's acid nickname for America.

But Adam Phillips taught me (this appears in many of his books, but perhaps most especially The Cure for Psychoanalysis) that ideological thinking is the antithesis of a psychoanalytic mind, and snobbery and defensiveness around it are both false to its promises and unnecessary to its survival (indeed, are fatal to its survival).

My Canadian and Catholic instincts here further remind me that many differences are frequently exaggerated, and a careful work of "translation" will often reveal how similar things are. Though I have often thought the contemporary academy (especially in the humanities) is too enamoured of works of intellectual genealogy, they have their place, perhaps especially in the clinical sciences as we see just how much covert borrowing there is, especially by those (e.g., Aaron Beck, Marsha Linehan) who had analytic training but went to great pains to downplay or disown it in order to promote or tolerate the spread of myths of their own putative originality.

Many concepts later "pioneered" (and trademarked and copyrighted) by others are demonstrably and indisputably analytic in origin. This is not noted smugly, but simply as a matter of honest intellectual history. Freud himself in several places notes how much he borrowed from others (Feuerbach, Schopenhauer), and I have myself noted his debts to monastic practices of late antiquity. There really is very little new underneath the sun.

So if, in what follows--some selective, non-systematic notes on the second edition of Miller's Motivational Interviewing, bought years ago but left mostly unread--you find my taking particular pains to relate these to my analytic training, or to find psychoanalytic antecedents and analogues, you will understand why. (Others have done this with greater skill than I--Glen Gabbard for one, including in this article; see also Stanley Messer here; and perhaps most especially D. Westen's 1998 article--showing how often extremely similar techniques are to be found in differently labelled theories under different terms.)

And the first note of significance comes at the start of the Acknowledgements page, where the authors note that "there is little that is truly original in motivational interviewing," referring to their debts to Carl Rogers in particular.

It is an interesting exercise to return to this book after having read the more recent treatment of effective therapists. For much of that latter book is foreshadowed in Motivational Interviewing, as when they note already on p.6 that across different theories and types of treatment, common factors "frequently make a difference," and these factors are bound up with "certain characteristics of therapists." Therapists who consistently manifest empathy, avoid being high-handed, and do not infantilize their patients have better outcomes than those who view it as their mission to engage in "confrontation" and advice giving.

I am also heartened that this book's second chapter is "Ambivalence: the Dilemma of Change." (Miller has a more recent book entirely on ambivalence.) Freud brought ambivalence to common awareness, though I sometimes fear it has largely disappeared from the clinical landscape, full as it often seems to be of much boosterish talk of techniques and tool boxes and work-sheets promising transformational change in 6 sessions or fewer (most of these barbaric self-promoters would write "less"). In any event, our authors note that ambivalence is universal and natural, and hectoring people who are ambivalent only serves to deepen the defenses and make change harder.

Instead of that, you need to see what does motivate someone, for we are all motivated by something, and often several things. Discover what continues to motivate your patient even as they remain ambivalently attached to the thing they are trying to give up or alter. And while you're about it, do not--these authors strongly suggest--be a purist about this but a pragmatist: how much of the thing are they willing to give up? Go with that rather than pushing for total abstinence or complete change. (I am heartened to read this, because it seems to accord with something I've been calling "partial victories" with my patients who are inclined to totalized thinking.)

Developing Discrepancy: Our authors note that discrepancy is a good thing, and sometimes may actively need to be cultivated. Help the patient come to see the gap between where they claim to want to be, and where they are now. This then leads into what is called "change talk," which manifests itself in four ways:

1) Recognizing disadvantages of the status quo

2) Recognizing advantages of change

3) Hope for change

4) Intention to change.

This leads the authors to recognize the entire process of motivational interviewing is one led by the patient, and not an imposition on them--or a panacea either. It takes time and patience, and consists in the clinician giving space to talk through the ambivalence and bring patients to decide for themselves what they want to do. (That, of course, sounds very much like the kind of free and freeing environment that most of us try to create in psychodynamic treatment, which resists imposing our ideas upon, and thus infantilizing, the patient.) As they say a little later, the key here is "exploration more than exhortation" (p.34), and the exploration and decision-making sees the patient very much in the lead.

All of this is premised upon something I have heard attributed to Rogers, and occasionally to Jung: "paradoxically, this kind of acceptance of people as they are seems to free them to change" (p.37). (So many people seem to come into my consulting room full of zeal for change which is motivated entirely by masses of self-loathing. They therefore find the idea of working from a place of self-acceptance utterly baffling.) Once people feel accepted as they are, and not forced prematurely into change by the therapist, then it is your next job with them to bring forward what they are already motivated by, and use that as a spring-board for action. Discovering a sense of self-motivation and self-efficacy will be key to everything that follows.

At the outset of treatment the authors warn clinicians off the use of questions--closed are worse than open-ended, but both invite superficial and often defensive answers. (Other traps to avoid: labelling, instructing, playing the expert, taking sides, blaming, and going to fast--what a friend of mine calls a failure of pacing).

At this stage, minimize the use of questions. Reflective listening and the use of statements are better. (In saying this, our authors remind me of Brodsky and Lichtenstein's useful article, "Don't Ask Questions.") Affirmation and elaboration are also useful techniques, particularly when the latter involves questions of values. Ambivalence can often be worked through if the desired change is in keeping with the patient's values.

Chapter 8: Responding to Resistance. I know that word has increasingly been avoided by some, but the authors note that no good alternatives have yet been found so they keep using it. Every time I hear it, I think of an example my first supervisor gave me. His besetting sin, he said, was getting too far out in front of the patient by moving too fast. He would look around and see how far behind him the patient was. Instead of chiding the patient for being a slow-poke, he realized he had gone too far too fast and had, he said, "humbly to walk back where they were and come along side them again." I think this example nicely illustrates Miller and Rolnick's ideas of resistance. Do not, they say, see this as something to blame the patient for: it is the fault of the clinician, just as my old supervisor recognized.

So what do you do--how ought you to respond? You meet resistance with non-resistance. Shifting the focus (what I've heard called "lowering the anxiety temperature in the room" by changing the subject) is useful, along with exaggerated (but calm and sincere) reflection back are useful here.

Ch.9: Enhancing Confidence: Not surprisingly, the authors recognize two traps at the outset to be avoided: one is to fall into the patient's totalized gloom-mongering and not have hope that things can change; the other is to be a mindless booster, offering cheap, soothing encouragement that is equally totalized and simplistic. You need to have and hold out hope for the patient, but it needs to be tempered and realistic hope. It also needs to be discerning enough that you know when to hope for change and when to gently bring the patient (as the Serenity Prayer reminds us) towards some reality-testing so they can see what is unlikely to change.

Having found realistic hope, the process next moves on to actual planning of the change--lists of ideas, desires, hopes, obstacles, and strengths. At every stage this is led by the patient and your job as clinician is not to be the expert dispensing advice or telling them what and how to do something. This is repeated, along with many of the observations briefly noted above, throughout the first half of the book, which is easily twice as long as it needs to be. Overall, the summary of MI's "four general principles" occurs early in the book (p.36), thus:

1) Express empathy

2) Develop discrepancy

3) Roll with resistance

4) Support self-efficacy.

Part IV: Applications of Motivational Interviewing features nearly a dozen chapters by invited contributors focusing on specialized populations (groups, couples, adolescents, criminals et al) or issues. There are also chapters reviewing the evidence on the efficacy of MI and its application in medical and other contexts.

Comments

Post a Comment